Dianne Feinstein: a complicated legacy for rivers

Senator Feinstein speaking at the 2007 Delta Summit in LA. Credit: CA DWR.

California’s senior U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein recently passed away after 31 years in the U.S. Senate. To say that she was influential on California water matters would be an understatement. I’ve prepared some personal recollections for Friends of the River.

Hetch-Hetchy: Senator Feinstein’s introduction to high-stake water and rivers games came when she was still the mayor of San Francisco. In 1987, the year that I joined the FOR staff, President Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior Don Hodel floated the idea of restoring Hetch-Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. She soon paid her first visit Yosemite and was calling O’Shaughnessy Dam and Hetch-Hetchy Reservoir “San Francisco’s birthright.”

She proved to be an influential politician, soon convincing Bay Area congressional representatives to block funding for studies by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to develop Hodel’s idea into a working proposal.

“San Francisco’s Birthright,” Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. Credit: CA DWR.

Establishing her role: After a failed run for Governor (in which she volunteered for a fascinating candidate interview with Friends of the River) she won a U.S. Senate seat in 1992. Senate traditions make the two U.S. Senators of a state influential in federal decisions regarding their state. Dianne soon worked out an arrangement with Barbara Boxer, California’s new U.S. Senator (taking office two months after Dianne), to handle the state’s water issues while Boxer worked on public lands issues — although Dianne picked up the legacy California desert bill from retiring California U.S. Senator Alan Cranston.

Dianne’s relationship with the San Francisco Public Utility District, various members of the Westlands Water District staff and board of directors, and the California water industry was enduring and rewarding, although she did occasionally disappoint them.

Auburn dam: For example, in 2001, after the Auburn dam battles of the 1990s, she wrote to Friends of the River that she was opposed to Auburn Dam.

This was nice to know, although by the time that she arrived in the Senate, FOR had managed to confine the Auburn dam votes to committees of the House of Representatives. Perhaps significant in that letter was the opposition to the dam by then newly elected Mayor Heather Fargo. Dianne had a soft spot in her heart for her fellow mayors.

It’s hard to say what truly happened between Auburn dam champion Rep. John Doolittle and the late Sacramento-area Representative Bob Matsui. However, Feinstein’s position may have played a role in Rep. Doolittle settling for some goodies for his congressional district instead of Auburn dam — while freeing Sacramento have the floodwater management projects they wanted.

An artist’s depiction of the Auburn dam, with the proposed dam location in the background. FOR archives.

Conflict on the lower American: The American River had been the subject of litigation for decades when the general manager of the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) began to practice some active listening with Sacramento area governments and environmental groups. During that time, Senator Feinstein telephoned a group of the parties to the dispute (including me) and invited (commanded?) us to join her to settle the dispute at her office in the Hart Senate Office Building. She spent a few hours with us, let us explain our perspectives, and let it be known that she expected these two regions that she represented to make peace.

After our time with her, we used the time to discuss pathways out of the dispute. It took many more conversations, but in the end EBMUD moved its diversion plans to not interfere with the state and federally designated wild & scenic lower American River. Instead it secured a more reliable drought supply from a diversion off the Sacramento River. Not perfect, but this little part of the water world is more peaceful now.

I must have stopped by the Senator’s office again that afternoon, since I remember walking her to her next meeting and discussing how she could mitigate the expected damage from the upcoming change in the federal administration. We had great ideas, but they did not come to fruition. Even Dianne Feinstein was not all-powerful.

Bay-Delta: One of the more powerful images that I have of Senator Feinstein was on the occasion of her announcement that she had hammered out an agreement for peace in our time over controversies involving the San Joaquin/Sacramento River/Bay Delta. She invited a large U.S. Capitol roomful of water agency leaders and their lawyers — and a small group of environmentalists — to receive the news.

She took the center seat along a long table with Republican members of Congress arrayed on each side of her and in front of her audience – a little like Jesus and his disciples in Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper. But after her optimistic announcement, Rep. Ken Calvert (R-Corona) spoiled the party and, looking out into the crowd and seeing me and the Environmental Defense Fund’s late Tom Graff, complained that he was “sick and tired of being invited to meetings with extreme environmentalists.”

Diane had to soothe Rep. Calvert’s feelings by vouching that we were not “extreme,” to Rep. John Doolittle’s (D-Rocklin) considerable amusement. The rest of the meeting quickly degenerated since few in the audience had been involved in any successful negotiations on this matter with her office.

I think Dianne was hoping that she could all bend us to her will, but we were a tough crowd and little fruit came immediately from that effort.

Morning poppies along the Merced river. FOR archives.

Playing on Senator Boxer’s turf: Republican control of the House of Representatives can invigorate some not-very-good ideas — including putting a reservoir on top of a national wild & scenic river.

Merced River wild & scenic river designation: Around 2010 to 2015, the Merced Irrigation District was actively working to expand their 32-mile-long reservoir footprint on the Merced River and onto the federal wild & scenic river upstream. They sequentially enlisted Rep. Jeff Denham (R-Atwater) and Rep. Tom McClintock (R-Elk Grove), who both managed to persuade the GOP-controlled House of Representatives to pass bills to prune away the lower end of the Merced River wild & scenic river designation.

Merced ID’s problem was the Senate, and partly, the division of labor between California’s two U.S. Senators. It did not take long before the District was waging a charm offensive on Senator Feinstein (and to some degree Senator Boxer). By April of 2013, Senator Feinstein was writing response letters to constituents telling them “that additional water storage may be possible without having a significant impact on the Wild and Scenic River designated portion of the river” and that she favored legislation to authorize the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to include a reservoir expansion study as part of its relicensing of Merced ID’s Exchequer Dam. Yikes!

Apparently Dianne believed that amending the National Wild & Scenic Rivers Act was no longer part of Senator Boxer’s public lands portfolio.

Behind the scenes, she was working hard to accomplish much more, something that stunned me during one of my Washington DC visits with her staff. Disturbing reports from some key environmental groups’ meetings with DC staff stunned me further.

She always loved her dams.

In the end some skilled lobbying, a little help from our friends, and just plain luck ended (for now) with a disappointed senior senator from California.

Reviving the Nation’s dam-building programs: But she would not be disappointed for long. The 2012 to 2016 California drought established the political conditions to pass the 2014 California Water Bond to set aside $2.7 billion of state taxpayer funds for new water storage projects in California.

Not to be outdone, Senator Feinstein worked to craft her “drought” legislation, the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act of 2016 (WIIN). Crafted with the advice and counsel of the Westlands Water District, the act (1) commanded the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to prioritize pumping from the Delta to water users in the south state (without violating the Endangered Species Act — quite a trick), (2) attempted to revive Reclamation’s 1930s-era taxpayer-subsidized dam-building programs, (3) set up a Reclamation program to fund dams proposed by others, (4) create a taxpayer funding mechanism to pay for this, and (5) established a program for Reclamation’s Central Valley Project water service contractors to secure permanent contracts with no acreage restrictions on property ownership.

Dianne had the muscle to attach the WIIN onto Senator Barbara Boxer’s Corps of Engineers Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) and pass it over Senator Boxer’s filibuster of her own bill.

The WIIN ideas have not died. The 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure bill (the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, or IIJA) built on the WIIN by continuing some of the dam-funding programs that expired with the WIIN in 2021.

Senator Feinstein used her last years in the Congress to make key features of the WIIN permanent — over objections from environmental groups. At the time of her death, these efforts had won some bipartisan support, received some hearings, but had not yet passed the Congress.

Taking down the Klamath River Dams: Senator Feinstein was on the side of the angels of the most significant dam-removal project of the western United States. While in the end, the heavy lifting came before FERC and not before the Congress, but her name as a supporter no doubt proved helpful.

The McCloud River. Credit: Tracey Diaz.

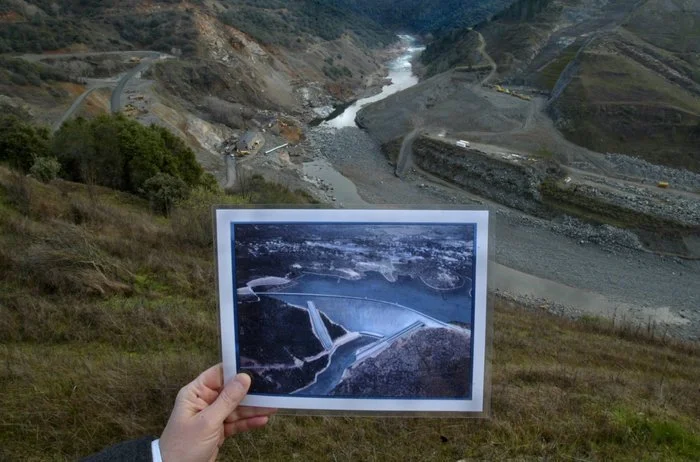

Overriding the state law and the California Wild & Scenic Rivers Act: Even two decades ago, Dianne was working for more or bigger dams. The State/Federal CALFED program included initial screening studies on a large number of dams, and more advanced studies on a handful of them, including two dam ideas with big conflicts with the State of California. Nevertheless, as early as 2004, she and Rep. Ken Calvert carried the legislation authorizing the studies.

These studies were as far as the two insoluble problem dams got. The proposed giant Temperance Flat Dam would be located on the fully appropriated San Joaquin River. No new state water rights are available on this river. The proposed expansion of the Shasta Reservoir on top of the McCloud River has been illegal since 1989 when the McCloud River became protected by the California Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

The Central Valley Improvement Act (passed just days before she became a U.S. Senator), the Reclamation Act of 1902, and the 1978 U.S. Supreme Court New Melones Dam decision all made Reclamation subject (in varying ways) to California law. Her 2016 WIIN Act continued that tradition.

During the Trump Administration, Reclamation and the Westlands Water District ignored that fact, moving the Shasta Dam raise into the design phase, and releasing a completed-but-not-truthful supplemental environmental impact statement. Presumably they were hoping that Senator Feinstein would reward their persistence. But she never did, and both projects are languishing, biding their time while the work is done to get more compliant Senators.

Of course, the former (for now) House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) has language inserted in the House Energy & Water Appropriation Bill that he hopes will eliminate the state’s McCloud River problem.

Although Senator Feinstein has passed, those of us who remain have some river protecting to do!