Some Dam Projects Stumble, Some Fall

Shasta Dam looms in the foreground, with a low reservoir level apparent in the background. Storage on this day was 1,469,736 acre-feet, 32% of total capacity. October 13, 2022. Credit: Andrew Innerarity for California Department of Water Resources.

There’s an unusual amount of news on California dams this month (some good news, or at least an opportunity for “I told you so” commentary), so put on your reading glasses and buckle up! But first let us start with a brief history.

Fueling the dam-building engine from state and federal taxpayer funds

When Friends of the River opposed Proposition 1, the California Water Bond of 2014, it was a lonely job. The popular Governor Jerry Brown, who was heading to his reelection bid without a viable opponent, devoted his campaign megaphone instead to securing a statewide ballot election victory for the bond.

The bond had been the product of a last-minute political compromise in 2009 among various factions within the legislature. The key for Republican and southern San Joaquin Valley Democratic legislators would be $3.0 billion for water storage projects, and without that, their votes would veto the larger bond package. Another key demand was that the money be controlled by the California Water Commission, appointed by the incoming and very much pro-dam Governor, and thus safe from interference by more environmentally inclined Democratic majority lawmakers.

After being delayed a few times because of the “Great Recession,” and taking a haircut to satisfy the newly elected Governor Brown’s frugal instincts (the storage subsidies went down to $2.7 billion), the bond got a 67% nod of approval in the statewide 2014 election (1).

Coupled with generous dam subsidies to be made available by Senator Dianne Feinstein’s “drought bill,” the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act of 2016 (WIIN), the long-frustrated dam proponents in California and the West were confident that it was now the dawn of a new dam-building era.

Lower McCloud Falls, a popular location for fishing, 2008. Credit: Steve Payer for Department of Water Resources.

The first stumbles — the Shasta Dam raise and the Centennial and Temperance Flat dams

The Water Commission soon set to work on regulations on how to spend the taxpayer funds it would control, and making decisions on who would be allocated the bond funds and for how much(2).

Protecting the McCloud River: The first bond funding supplicants to fall were the aspiring beneficiaries of the proposed 650,000-acre-foot Shasta Reservoir expansion when in late 2016 the Commission adopted regulations proposed by its staff (and Friends of the River) to reaffirm the bond language (also inspired by Friends of the River) prohibiting spending bond funds for dams illegal under the state and national wild & scenic river acts. (The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation had urged the Commission to adopt regulations permitting funding for this project)(3).

Centennial dam: In May of 2018, rejecting a last-minute plea from the Nevada Irrigation District, the Commission affirmed the conclusions of its staff that the application for any subsidy for the proposed, and controversial, 110,000-acre-foot Centennial Reservoir on the Bear River failed to pass muster under the Commission’s funding rules(4).

Temperance Flat dam: By July of 2018, the Commission finally met to decide which dams and the funding allocations they would receive. Four proposed dams got funding allocations. While the proposed $2.8 billion, 1.3-million-acre-foot Temperance Flat dam on the fully appropriated San Joaquin River got an allocation, Fresno area politicians widely regarded the $171 million allocation as a crushing defeat for their project(5).

By June 2020, the Temperance Flat Reservoir Authority conceded that it could not finance the dam(6), and later that year the Commission took back the dam’s allocation and soon redistributed its allocation to the remaining three other eligible dams and four groundwater projects(7)(8).

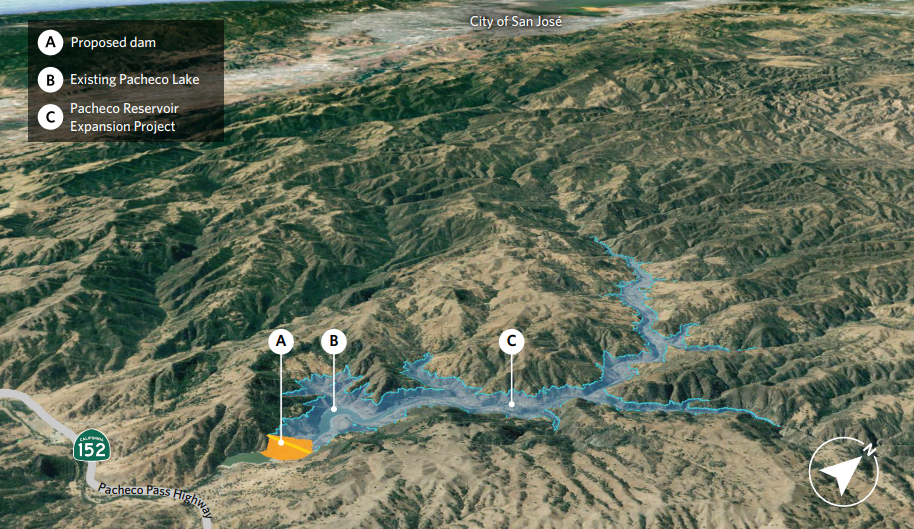

Project rendering of proposed Pacheco dam and reservoir as of May 2023. Credit: Valley Water.

The Pacheco dam stumbling with cost overruns but still lingering

Pacheco Dam: By 2021, things were becoming difficult for the Santa Clara Valley Water District’s proposed $1.0 billion, 140,000-acre-foot reservoir to be built on the Coast Range’s Pacheco Creek, nestled between the Santa Clara Valley and the San Luis Reservoir.

While the Commission’s allocation had neared a 50% subsidy for the then billion-dollar dam, seismic concerns had caused the dam’s projected costs to balloon to almost $2.5 billion, leaving the District (“Valley Water” for short) with a $2.0 billion bill if it wanted to build the dam(9). Valley Water also failed to attract partners. It looks like it will have to go it alone.

Contributing to its problems, Valley Water was also proposing to move the dam and resulting reservoir upstream. That would put the upper part of the reservoir in Henry Coe State Park(9), which Valley Water confidently asserts is perfectly legal in spite of its obvious conflicts with state law.

Valley Water has passed a local ballot measure giving it the authority to raise water rates to finance this and other projects, but it has yet to bite this $2 billion bullet. “Making your water more expensive” is not always a good campaign slogan for an Board member running for election.

Los Vaqueros Dam, 2008. Credit: CA Dept. of Water Resources.

Unexpected and perhaps fatal stumble, the Los Vaqueros Dam raise

The Contra Costa Water District’s Los Vaqueros Dam sits awkwardly in the inner Coast Range foothills of Contra Costa County. Raised once previously, the 160,000 acre-foot reservoir was proposed to get expanded again, this time to 275,000 acre-feet of storage capacity.

In 2018, the Commission had allocated $477 million to the $980 million project, but by 2024 project costs had risen to $1.6 billion, and by the week of September 24, 2024, the deal among Bay Area water agencies to jointly finance and share water from the project had broken down. The District was not prepared to finance the project on its own. The project appears slated for mothballing(10).

Water industry commentators, of course, suggest that more state taxpayer subsidies could revive the project. However, if the taxpayer’s pockets are not to be further picked, the Commission will likely be under pressure to find a way to reallocate its funding allocation commitments to its other remaining storage projects.

And as much as the Commission may hate it, the Commission may find that fully reallocating its funding commitments from failed projects to its remaining ones will not be legally possible, especially if other eligible projects stumble badly and the Commission becomes awash with cash that it cannot spend. In that event, the currently sequestered state taxpayer funds could effectively be returned to the state general fund.

The Bear River, sometimes considered a sister river to the Yuba River, was the proposed location of Centennial Dam. Credit: Placer County.

Centennial dam to be mothballed

September 2024 was proving to be eventful. A staff report to the Nevada Irrigation District Board of Directors suggested that the proposed 110,000-acre-foot Centennial dam reservoir on the Bear River was not a good investment for the District. Rather, another idea, raising the existing Rollins Reservoir, looked like a better fit for the District.

The Board accepted the inevitable and mothballed the project. It also announced that it was withdrawing its water rights application for the dam(11).

There will no doubt be a party or two or three this year in Nevada City hosted by the South Yuba River Citizens League and the Friends of the Bear River. Stay tuned for that.

No doubt, of course, among the celebrants, someone will come with the reminder that dam proposals, even if buried and in the grave, can reemerge like zombies to haunt future generations. Never forget that.

The rock formation pictured here, also known as "Del Puerto," is located near the city of Patterson. "Del Puerto" is the proposed location of the Del Puerto Canyon Dam. Credit: KM.

Consequences at the Water Commission?

The Water Commission is deeply committed to disbursing the $2.7 billion under its control (what the Governor wants, he gets). When the Temperance Flat dam proposal collapsed, the Commission reallocated the Temperance Flat dam funding allocation to some water storage projects for which the Commission had underfunded and as an inflation-adjustment bonus to the remaining eligible storage projects(8). (Proposition 4, the “Climate Bond” on this year’s statewide ballot, allocates $75 million for the same purposes.) Bumping up the allocations with any “recovered money” remains an option for any projects that have funding allocations that are less than their Commission-declared funding eligibility, but there isn’t a lot of remaining eligibility left — unless the Commission changes its regulations to go on the hunt for previously undiscovered funding eligibility for its eligible projects.

Another option for the Commission is to encourage the Del Puerto Water District to apply for funds for the District’s proposed $750-million-dollar, 82,000 acre-foot Del Puerto Canyon dam in the Coast Range foothills west of Patterson. In December 2021, on a split vote, the Commission grandfathered the project’s potential eligibility (12), but with all the funds already spoken for, the District has had no incentive to prepare an allocation application. (Don’t grieve too much, however. They have other pockets to pick: they may be eligible for a subsidy of up to 25% of project costs under Senator Feinstein’s “drought bill”).

In any event, if more of the 2014 California Water Bond money remains unspent, the Del Puerto Canyon dam could be rescued from cold storage and have its chance to bask in the sun of big Water Commission grants — although the sponsors of the multi-billion-dollar Sites Project, already basking in the glow of nearly a billion dollars of Commission funding allocations will no doubt also be casting a covetous gaze on any serious unspent money.

More dam news

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is undertaking a $1.1 billion seismic upgrade of its B.F. Sisk (San Luis) Dam near Pacheco Pass. A good idea. However, it has proposed to make the dam available for a $900 million 130,000-acre-foot storage augmentation project as a later phase of the seismic project. The storage expansion would be subsidized by a 30% WIIN grant.

At present, the federal agricultural contractors have declined to participate. The Santa Clara Valley Water District has tentatively agreed to buy 60,000 acre-feet of that storage. Presumably, if the reservoir expansion is to move forward, the remaining 70,000 acre-feet of storage will have to come from other “partners” and the total offerings from the supplicants be enough to cover the considerable cost of the expansion(13).

We await the outcome of this battle among the green-eyeshade back-room crowd.

Some concluding thoughts

The entire litany described here does demonstrate that the bean counters in the back room often make the real decisions — something that deadbeat dams can sometimes experience at their peril.

Resources

(2) CA Water Commission Prop 1 Press Release

(3) FOR Shasta Dam Raise Fact Sheet

(4) The Union: Centennial Ineligible for State Funding

(5) Fresno Bee: Valley Leaders Won’t Give Up on Temperance Flat Dam

(6) SJV Water: Temperance Flat Dam Doesn’t Pencil Out

(7) Fresno Bee: Temperance Flat Dam Returns $171M to State

(8) CA Water Commission increases potential funding for 7 water storage projects

(9) Mercury News: Pacheco Price Tag Doubles

(10) Environmental groups comment on CA Water Commission findings on Pacheco, etc.

(11) The Union: NID Board votes to pull Centennial application

(12) CA Water Commission: Four projects pass Prop 1 milestone

(13) Fresno Bee: Huge San Joaquin Valley Reservoir is Expanding - The Water is Headed Elsewhere